Biography of Antonín Dvořák

“I am but an ordinary Czech musician [...] and despite acquiring some degree of renown in the world of music, I will remain just what I have been – a simple Czech musician.”

In the past, the music of Antonín Dvořák (1841–1904) was often dubbed “patriotic”, “spontaneous and joyful”, but in reality, it is much more sophisticated. It is rooted in Czech musicality and is extremely rich in its palette of musical themes. The basic features of Dvořák’s distinctive style are invention, varied rhythms, colourful orchestral sound, precise sophistication of form and depth of expression. From the initial inspiration from Viennese Classicism, his constant search for new paths brought him to the brink of emerging impressionism. He significantly affected the fields of symphonic, chamber, vocal and vocally instrumental music and music drama. A happy family background, a firm working routine and tenacity enabled him to compose systematically and regularly, which resulted in more than 200 works. Dvořák paved the way for Czech modern music and raised a generation of his followers.

Antonín Dvořák was born on 8 September 1841 in Nelahozeves to František and Anna Dvořák as the first-born of nine children. The Dvořák family was well established in this region. They were mostly small farmers and tradesmen. Dvořák’s father owned a butcher’s shop and an inn in the village but was mostly struggling to keep his business alive. He was a music lover and an avid amateur musician – he had a license to play the zither and accordion in the inn he ran. Although Antonín occasionally had to help his father in the butchery after school, František did not force his gifted son to follow him in the craft. The widely accepted claim that Antonín trained as a butcher was refuted by the discovery of Dvořák’s forged butcher’s guild apprenticeship certificate. František was also said to be Dvořák’s first music teacher. But it was Josef Spitz, a teacher from Nelahozevec, who took over Dvořák’s music education at the beginning of Dvořák’s schooling. Very soon, the gifted boy became a singer and a violinist in a local Nelahozeves choir and occasionally helped accompany Holy Mass in the surrounding villages. There is also a story about how a little violinist amazed the guests of his father’s inn during a performance by a local band.

Antonín Dvořák's birthplace in Nelahozeves, around 1900, © National Museum - Antonín Dvořák Museum

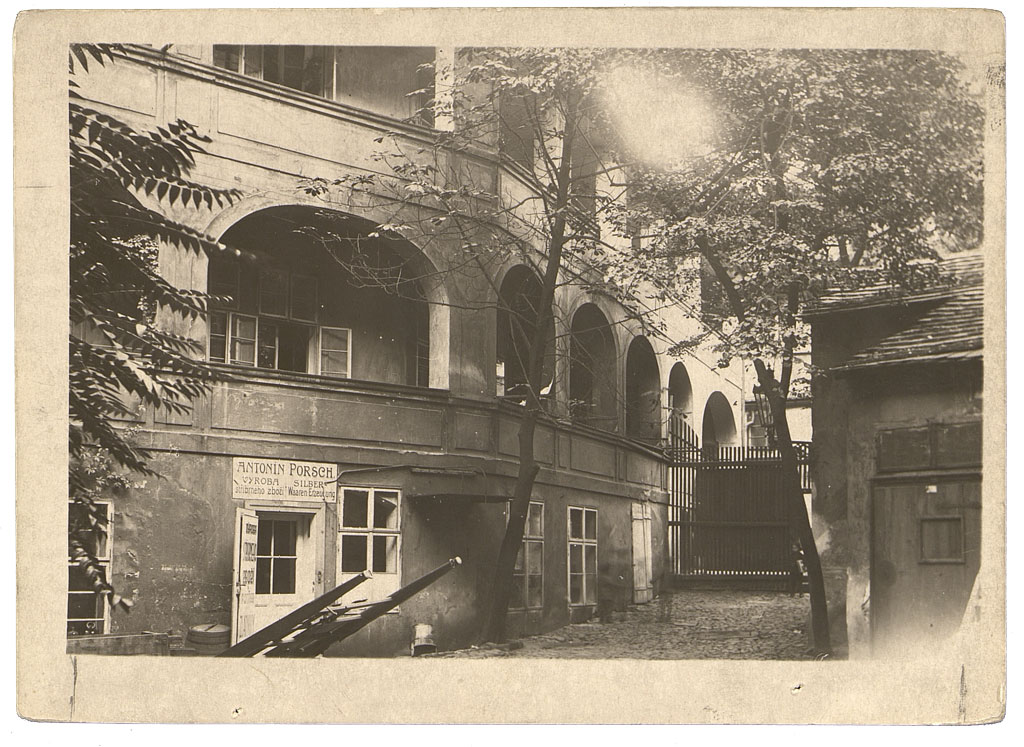

Dvořák’s future musical direction was probably decided after he finished primary school in Nelahozeves in 1853. The talented 12-year-old boy was sent to relatives in nearby Zlonice to better his musical skills with the renowned musician Antonín Liehmann, and probably also to make it easier for his father to take care of a large family. The strict cantor, who punished every playing mistake with a slap, taught the composer-to-be the basics of the indispensable basso continuo, harmony and improvisation. In addition to the organ and piano, Dvořák also attended violin and viola lessons, which he made practical use of not only at church, but also as a member of Liehmann’s band. Aa short stay in Česká Kamenice, where he improved his skills in German alongside further musical training, was followed by a trip to an organ school in Prague, a journey to independence and the musical profession. During his two-year studies at the organ school (1857–1859), where the language of instruction was only German, Dvořák studied practical organ playing, consisting of modules labelled “independent improvisation” and “study of organ compositions”. On the day of his graduation performance in July 1859, Dvořák played Bach’s Prelude and Fugue in A minor and two compositions of his own, Prelude in D major and Fugue in G minor. In addition, he also performed a four-hand arrangement of Bach’s Fugue in G minor with his classmate Sigmund Glanz. Dvořák was almost eighteen years old, he intensely observed all the stimuli of musical Prague and was soon to stand on his own two feet.

Organ School in Prague, 2nd half of the 19th century, © National Museum - Antonín Dvořák Museum

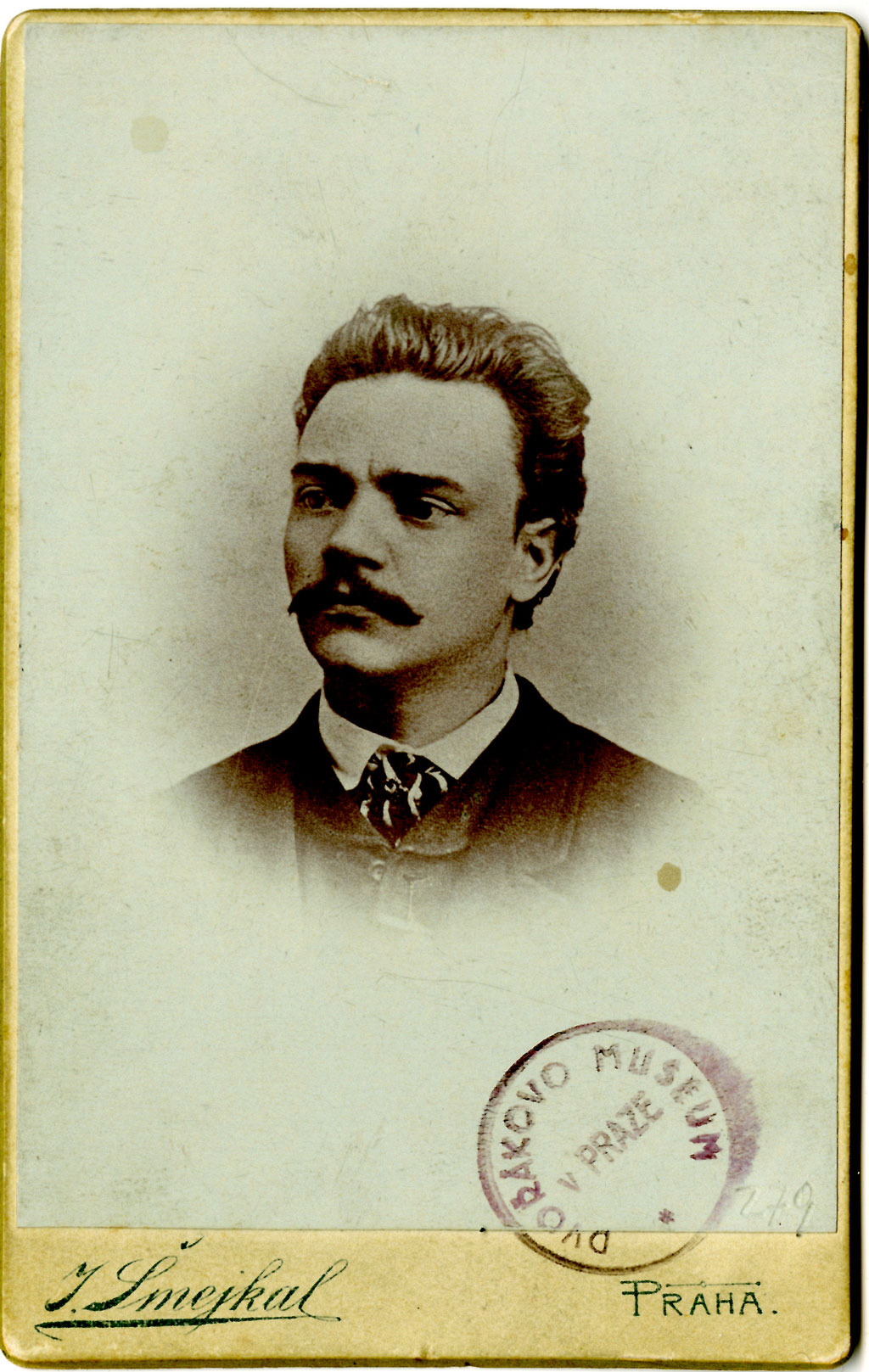

He was, however, unsuccessful with his application for the position of organist at the Church of St. Henry in Prague and so he stayed at the position of violinist in the band of Karel Komzák, where he enrolled probably in September after graduating (before that he played in the Prague orchestra of the Cecil Union). The band played in Prague at dance parties, in restaurants and on promenades, and after the opening of the Czech Provisional Theatre in 1862, the members of the ensemble moved to the theatre orchestra, in which Dvořák himself remained for almost nine years (until 1871). His first compositions were written at this time, some of which he unfortunately later disposed of. He was nearing his twenties when he assigned his first opus number to String Quintet in A minor from 1861. Soon after, he wrote Symphony No. 1 in C minor, referring with its subtitle — “The Bells of Zlonice” — to the joyful period of his childhood and adolescence. And because as a player of a theatre orchestra he had a great knowledge of operatic repertoire, he started composing operas (the first two operas Alfred and The King and the Charcoal Burner, Op. 14).

Antonín Dvořák, studio of J. Šmejkal, Prague, around 1868 © National Museum - Antonín Dvořák Museum

His unhappy love for Josefína Čermáková, the daughter of a Prague goldsmith, whom Dvořák gave private piano lessons, was reflected in a cycle of love songs named Cypresses to the lyrics by Gustav Pflegr-Moravský. We do not know whether the young music teacher was able to openly express his feelings to Josefína at that time, but the young actress of the Provisional Theatre later married Count Václav Kounic and Dvořák married her younger sister Anna eight years after writing the Cypresses (1873). It was a fortunate period for Dvořák; his first major compositional success — the première of the patriotic hymn The Heirs of the White Mountain, Op. 30. Encouraged by that, he composed two symphonies (Nos. 3 and 4), three string quartets and a new opera entitled The Stubborn Lovers, Op. 17.

Sisters Anna (seated) and Josefina (standing) Čermák at the piano, studio of Moritz Klemperer, Prague, undated © National Museum - Czech Museum of Music

However, the family’s financial situation was no bed of roses. This improved in 1875, when Dvořák applied for a state-paid scholarship for young, talented and poor artists. With an application submitted to the Ministry of Cult and Education in Vienna, Dvořák succeeded not only for the first time, but also in the next four years. The fourth application in 1877 was of extraordinary importance to the composer. He enclosed the Moravian Duets, Opp. 20, 29, 32 and 38, which enchanted one of the jurors, the well-known composer Johannes Brahms, who recommended the compositions to his Berlin publisher Fritz Simrock for publication. Dvořák certainly knew that this was a unique offer from the publishing house. What he probably did not know, however, was the fact that this marked the beginning of a very successful lifelong collaboration with Simrock. The sudden success was nonetheless outweighed by tragic events in the family. In the same year, two of his children, the almost one-year-old Růženka and the three-and-a-half-year-old Otakar, died in a very short time, while two years prior to these tragedies, a newborn Josefka also tragically passed away. In response to this misfortune, the composer returned to the previously begun composition Stabat Mater, Op. 58.

After overcoming this difficult situation, the joyful expectation of other descendants (Dvořáks had six more children) gave rise to a prolific period that brought us Slavonic Dances, Opp. 46 and 72, Slavonic Rhapsodies, Op. 45 and Czech Suite, Op. 39, among others. In the early 1880s, the composer was given another great opportunity, which secured his world renown. Dvořák, already known in England for his Slavonic Dances , received an invitation from the London Philharmonic Society to conduct some of his works. After the first visit, during which he conducted works such as Stabat Mater or Symphony No. 6 in D major, Op. 60, another eight trips to England followed until 1896. Music festivals and institutions commissioned works which the composer usually conducted at the première, such as Symphony No. 7 in D minor, Op. 70 for London, the oratorio Saint Ludmila, Op. 71 for the Leeds Festival or the cantata The Spectre’s Bride, Op. 69 and Requiem, Op. 89 for the Birmingham Triennial Music Festival. The English performances of Dvořák’s works were magnificent, with a large cast of choir and orchestra, which the composer had not previously encountered:

“There are 250 sopranos, 160 altos, 180 tenors and 250 basses; in the orchestra, the main voice is realised by: 24 lead violins, 20 second violins, 16 violas, 16 cellos, 16 double basses. The impression of such a huge body was truly enchanting.”

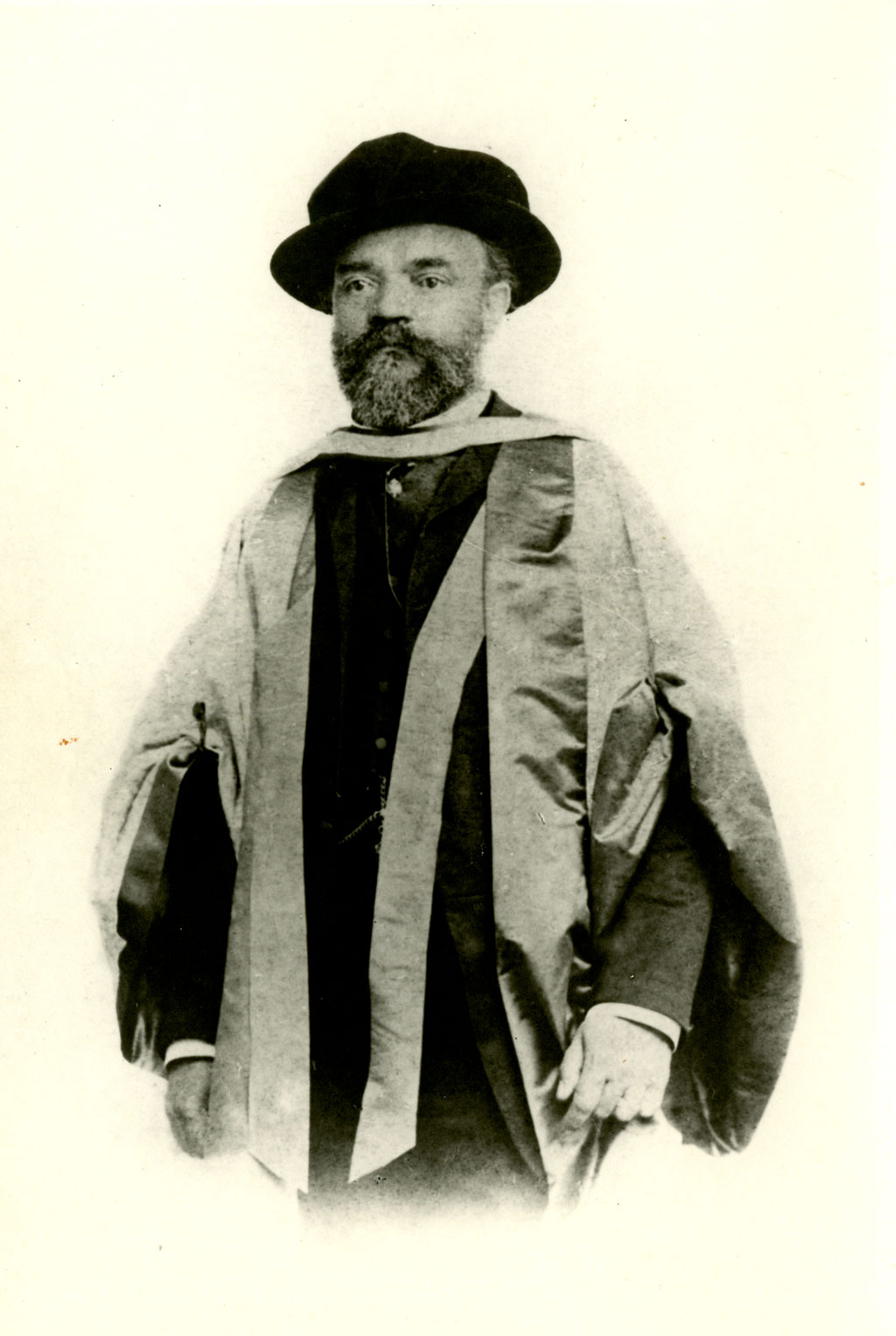

Dvořák’s host and guide was Alfred Littleton, a prominent publisher and the co-owner of Novello, Fewer and Company, with whom Dvořák collaborated, much to Fritz Simrock’s displeasure. Littleton was also a promoter of Dvořák’s work in England and an important mediator in negotiating the composer’s future journey to the “New World”.

Dvořák in robe from his graduation in Cambridge (doctor honoris causa), studio of J. Tomáš, Prague 1891 © National Museum - Antonín Dvořák Museum

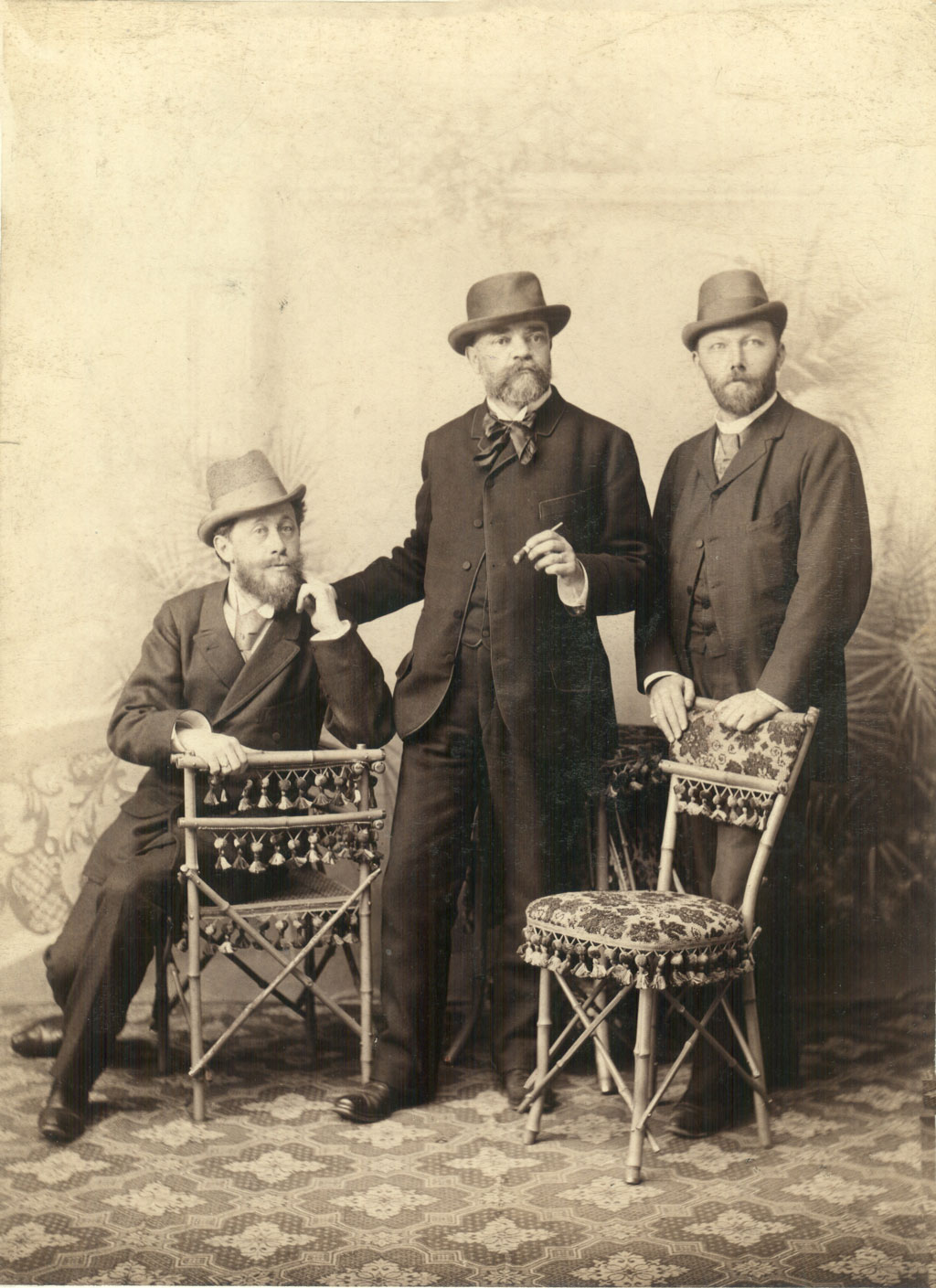

Word of Dvořák’s success in England spread across the ocean to the United States. Experienced musicians from Europe often performed very well there, usually landing important positions within music institutions. Dvořák was no exception to this rule; the president of the National Conservatory of Music of America in New York, the enlightened and ambitious Jeanette Thurber, wanted the composer for the position of school principal, but also as a personality who possessed the right skills to, in Dvořák’s own words, “create national music”, that is, a school of modern American composition. She decided to offer the composer a very lucrative deal for the position of school principal for two years, including the conducting of six concerts from his repertoire. Although it was not easy for Dvořák to leave home and thus split his family, he eventually accepted the position. Before setting forth for a challenging journey overseas, he did a farewell tour around Bohemian and Moravian cities, which he completed together with friends — cellist Hanuš Wihan and violinist Ferdinand Lachner. The composer himself performed in this trio as a pianist.

Antonín Dvořák with violinist Ferdinand Lachner and cellist Hanuš Wihan, studio of J. L. Šolc, Brno 1892 © National Museum - Antonín Dvořák Museum

He began the school year of 1892–1893 as the principal of the New York Conservatory. It was an exceptional school. In addition to African Americans, girls could study at school, and poor students could apply for scholarships. Dvořák taught, conducted the school orchestra and composed in his spare time. The idea of using African American music for a new American school of composition was advanced via Thurber by the American press, and Dvořák himself provided journalists several statements on the matter:

“I am now convinced that the future music of this country must be based on what are called negro songs. These must become the real foundation of any serious and original compositional school to be established in the United States. These beautiful and diverse songs are the fruit of this country. They are American.”

He expressed his impressions of the New World in the famous Symphony No. 9 in E minor, Op. 95 with the subtitle “From the New World.” Other compositions inspired by America were created there, such as String Quartet No. 12 in F major, Op. 96 “American”, or String Quintet No. 3 in E flat major, Op. 97 and Biblical Songs, Op. 99 based on texts from King David’s Book of Psalms. He also began work on Concerto for Cello in B minor, Op. 104, which the composer completed only after returning to Bohemia. He composed some of the works in the summer of 1893, which he spent with his whole family in the American countryside in Spillville, accompanied by his friend, the Czech American Josef Kovařík.

Stereoscopic photograph of Dvořák's family and friends in New York, 1893, photo by A. Baštýř © National Museum - Antonín Dvořák Museum

After returning from America, Dvořák was employed at the Prague Conservatory, of which he became director in 1901. In the field of composition and conducting, he rejected numerous contracts. He wanted to rest and compose only what he wanted, that is, symphonic poems and operas, as he himself wrote:

“...I am ever so happy that after such a long rest, I can work again on what I want and not what others want.”

For symphonic poems based on Erben’s A Bouquet (The Water Goblin, Op. 107, The Noon Witch, Op. 108, The Golden Spinning Wheel, Op. 109 and The Wild Dove, Op. 110), Dvořák used the meter and declamation of Erben’s verses to make the orchestral melody suggest a notional vocal line. In addition, he devoted himself more intensively to opera. His last three operas on fairy tale themes, The Devil and Kate, Op. 112, Rusalka, Op. 114, and Armida, Op. 115 symbolically conclude the composer’s oeuvre. The stress from rehearsing for the première of Armida in 1904 and its impromptu staging contributed to a kidney attack that forced the composer to leave the theatre during the première. The illness was complicated by flu and the common cold, and after resting in bed, the composer suddenly died on 1 May, 1904.